Beyond Bletchley

The Real Story of Alan Turing and the Team That Changed Computing

The mythology of genius loves a solitary figure. Alan Turing, hunched over an Enigma machine at Bletchley Park, single-handedly saving Western civilization—it makes for compelling cinema. The 2014 film The Imitation Game introduced millions to Turing’s name and tragic fate, cementing this image of the lone genius battling bureaucracy and winning the war through pure intellectual force.

The reality was messier, more international, and infinitely more interesting. Turing was brilliant, certainly. But the breaking of Enigma began years before he arrived at Bletchley Park, in the mathematics departments of Warsaw. It required thousands of volunteers intercepting radio signals across the British Empire. It depended on French intelligence shuttling secrets between nations as Europe collapsed into war. And it worked because Bletchley Park accidentally created the kind of collaborative culture that Silicon Valley would later try—and mostly fail—to replicate.

To understand what Alan Turing actually accomplished, we need to start not in Cambridge or at Bletchley, but in Warsaw in 1920.

The Polish Foundation

In August 1920, the Red Army stood at the gates of Warsaw. The newly independent Poland faced annihilation, and with it, the potential fall of Western Europe to Bolshevism. What saved Poland that day was partly military strategy, partly desperate courage—and partly cryptography. Polish intelligence had been intercepting and decoding Soviet radio communications, giving Polish forces crucial insights into enemy movements and intentions.

This early success planted something in Polish military thinking: radio interception and codebreaking weren’t just useful—they were existential. When commercial Enigma machines appeared in the 1920s, Polish intelligence immediately understood their significance. By 1932, the Biuro Szyfrów (Cipher Bureau) had recruited three brilliant young mathematicians—Marian Rejewski, Henryk Zygalski, and Jerzy Różycki—to attack the problem.

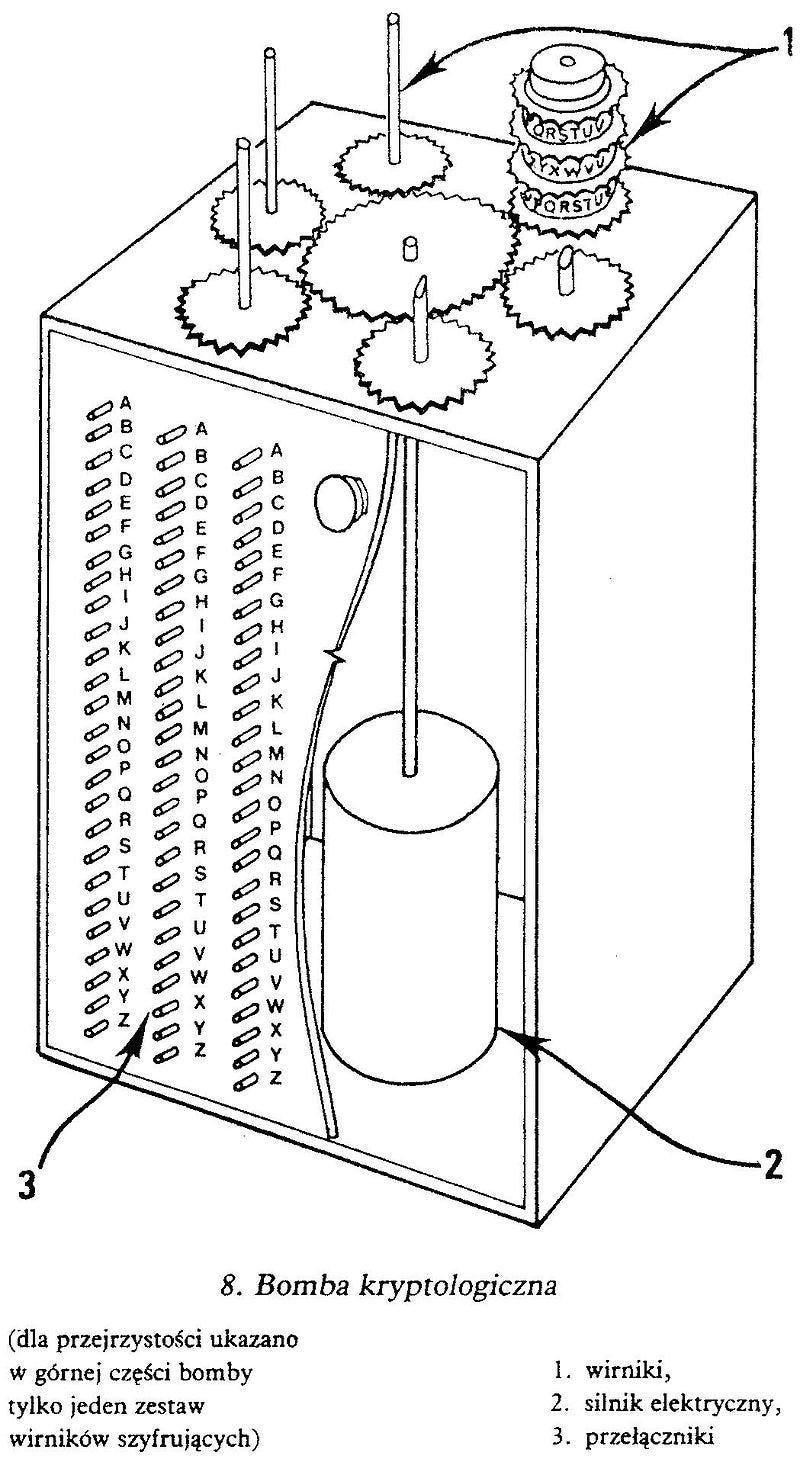

What they accomplished over the next seven years is staggering. Using pure mathematics and remarkably little raw data, they broke early versions of Enigma. Not by guessing. Not through espionage (though the French Secret Service did provide crucial cribs). But through rigorous mathematical cryptanalysis. Rejewski reconstructed the internal wiring of the Enigma rotors using group theory and permutations. Zygalski developed his famous “sheets”—perforated paper tools that could identify possible rotor positions. Różycki contributed to the bomba kryptologiczna, an electromechanical device that automated part of the search process.

By 1939, as war loomed, the Poles had been reading German military communications for years. But they also knew something the Germans didn’t: Poland would soon be occupied. In July 1939, in a secret meeting outside Warsaw, Polish cryptographers handed everything—their methods, their mathematics, their machines—to British and French intelligence. It was one of the most consequential intelligence transfers in history, and it has largely been forgotten.

The 1979 Polish film Sekret Enigmy tells this story, though it remains little-known outside Poland. When The Imitation Game credits Turing with “breaking” Enigma, it elides a crucial truth: the Poles had already broken it. What remained was a different problem entirely.

The Turing Machine: Foundations Before the War

Before Turing ever thought about Enigma, he had already revolutionized computer science—three years before the first programmable computer was built.

In 1936, Turing published “On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem.” The paper addressed a question posed by mathematician David Hilbert: could there exist a mechanical procedure to determine whether any given mathematical statement was provable? Turing’s answer was no—and his method of proving it changed everything.

He invented a purely hypothetical machine: an infinite tape marked into squares, a read/write head that could move along the tape, and a set of rules determining how the machine should respond to what it read. This “Turing machine” could, in principle, compute anything that could be computed. Turing showed that certain problems—like Hilbert’s Entscheidungsproblem—were fundamentally uncomputable. No machine, no matter how sophisticated, could solve them.

The paper is foundational, but not easy reading. For those wanting to understand it deeply, Charles Petzold’s The Annotated Turing makes the work accessible, walking through Turing’s argument step by step. It’s a masterclass in how to read a seminal mathematical paper, and for anyone interested in the foundations of computer science, it’s indispensable.

From September 1936 to July 1938, Turing studied at Princeton University under Alonzo Church, who had independently reached similar conclusions about computability using lambda calculus. Church gave Turing’s concept the name “Turing machine,” and the convergence of their work—what’s now called the Church-Turing thesis—established the theoretical limits of computation before anyone had built a general-purpose computer.

At Princeton, Turing also encountered John von Neumann, already world-famous at 31. When Turing completed his PhD in 1938, von Neumann recognized his brilliance and offered him a position as research assistant at the Institute for Advanced Study for $1,500 a year. Turing declined. War was coming, and he wanted to return to Britain. Had he accepted, the trajectory of World War II might have been different—Britain would have lost one of its key codebreakers.

The 1996 film Breaking the Code captures Turing’s ability to make these abstract ideas concrete. In one scene, asked to explain his work “in general terms,” Turing describes his machine with characteristic clarity: a device that could follow rules, one step at a time, and through those simple operations, perform any possible computation.

It’s a brilliant scene, though there’s an irony to it: Turing explains it as clearly as humanly possible, but without a certain level of mathematical sophistication, you still can’t quite grasp what makes the idea revolutionary. That gap—between clarity of explanation and depth of understanding—is part of what makes Turing’s achievement so remarkable.

This matters because when Turing arrived at Bletchley Park in 1939, he wasn’t starting from scratch. He already understood, at a fundamental level, what mechanical computation meant. He knew its possibilities and its limits. The Turing machine wasn’t yet real, but the theory was sound. All that remained was to build it.

Bletchley Park: Industrializing Polish Mathematics

The problem Turing inherited in 1939 was different from the one the Poles had solved. Yes, they’d broken Enigma—but the commercial version, with three rotors and limited key space. By 1939, German military Enigma had added complexity: more rotors, a plugboard that created trillions of possible settings, and new variants like the naval Enigma with four rotors. Worse, the Germans changed settings daily.

The Polish mathematical methods still worked in theory. In practice, they were too slow. You needed to test vast numbers of possible rotor positions against known plaintext patterns (”cribs”—phrases likely to appear in messages). The Poles’ bomba could do this, but not fast enough for wartime needs.

Turing’s innovation was to mechanize probabilistic reasoning at industrial scale. The “bombe” machines he designed—building directly on the Polish bomba concept—didn’t try every possible setting. Instead, they used logical inference to constrain the search space. When a crib produced a logical contradiction in one rotor configuration, that configuration could be eliminated. The bombes systematically checked configurations against known patterns, hunting for settings that remained logically consistent while ruling out millions of impossibilities.

This was computational statistics in practice, even if the formal theory was still developing. Turing took the kind of probabilistic reasoning mathematicians had been using on paper and made it mechanical, fast, and tireless. The bombes were engines of logical elimination, exploring vast search spaces through systematic inference.

By 1944, Turing had moved on from Enigma entirely, working on speech encryption for the Delilah project. The Enigma problem had been industrialized and handed to others. His contribution had been to bridge theory and practice—to take Polish mathematics and his own understanding of computation and build machines that could actually do the work at the speed war demanded.

The Invisible Infrastructure: Y Service

Here’s what every documentary about Bletchley Park elides: you can’t break codes if you don’t intercept messages. And intercepting messages at the scale World War II demanded was a staggering logistical challenge.

Enter Y Service—the network of thousands of radio operators, many of them volunteers and many of them women, who listened to Axis communications 24 hours a day across hundreds of listening posts from Scotland to Gibraltar to India. They transcribed encrypted messages, often under difficult conditions: weak signals, atmospheric interference, jamming. They logged call signs, frequencies, timestamps—metadata that helped cryptanalysts identify networks and priorities.

The scale is difficult to comprehend. Thousands of operators. Hundreds of thousands of intercepted messages. Constant quality control to ensure accurate transcription. Prioritization to identify which messages mattered most. All of this before a single codebreaker looked at the data.

Sinclair McKay’s book The Secret Listeners tells their story, and it’s a revelation. These weren’t passive receivers—they were active hunters, developing techniques to identify networks, track ships, and predict where valuable intelligence might appear. Their work determined what was possible at Bletchley. Without them, Turing’s bombes would have had nothing to process.

Bletchley’s Accidental Culture

What made Bletchley Park work wasn’t just Polish mathematics and Turing’s machines and Y Service’s data streams. It was culture—the kind of culture that emerges when you throw out normal hierarchies and let brilliant people organize themselves.

Military discipline? Mostly ignored when it got in the way. Rigid command structures? Flattened. The place ran more like a Cambridge college than an army base. Veterans remembered it as “the best boarding school”—intense intellectual work during shifts, then drama societies, chess clubs, orchestras, and dances. There were romances, rivalries, friendships forged under pressure. And underneath everything, the weight of secrecy: you couldn’t tell your family what you did, couldn’t explain why it mattered, couldn’t share the burden.

Sinclair McKay’s The Secret Life of Bletchley Park captures this world beautifully. What emerges is something Silicon Valley has tried to replicate for decades: a genuinely diverse team (by 1940s standards—women mathematicians, working-class linguists, aristocratic eccentrics) given autonomy, hard problems, and adequate resources. Not ping-pong tables and free snacks. Something deeper: trust in competence over credentials, cross-disciplinary collaboration because the problem demanded it, and the freedom to organize work around the work itself rather than around someone’s theory of management.

This matters because breakthrough rarely happens in isolation. You can have individual genius—Turing certainly qualified—but turning genius into impact requires infrastructure, collaboration, and culture. Bletchley proved you could manufacture those conditions, at least when saving civilization provided sufficient motivation.

The Turing Test: Brilliant, Personal, and Obsolete

In 1950, Turing published “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” The war was over. Enigma remained classified (it wouldn’t be publicly known until the 1970s). Turing had moved on to thinking about whether machines could think—and he approached the question with characteristic cleverness.

“Can machines think?” was, Turing argued, too vague to answer. It led immediately into philosophical morass: what is thinking? What is consciousness? What is understanding? Instead, he proposed a different question: could a machine convince a human interrogator that it was human?

The test—the famous “imitation game”—was elegantly simple. An interrogator converses via text with two entities: a human and a machine. If the interrogator can’t reliably distinguish between them, the machine passes. Turing predicted machines would pass by 2000.

Andrew Hodges’ magisterial biography Alan Turing: The Enigma reveals something most accounts miss. Hodges, writing in the 1980s as a gay rights activist, saw what others overlooked: the test had a deeply personal dimension.

Being gay in 1950s Britain—where homosexuality was criminalized—meant performing heterosexuality every day. Every interaction was a test: could you pass as “normal”? Could you convince the interrogator you were what they expected? Success meant invisibility, safety through imitation. The parallels to Turing’s philosophical test are striking: in both cases, the question is whether imitation of humanity makes you human, or whether something essential is lost in the performance.

We can’t imagine what that was like—how exhausting, how corrosive to live a life of constant performance. The Turing Test, viewed through this lens, isn’t just abstract philosophy. It’s autobiography.

Turing attended Ludwig Wittgenstein’s lectures on the foundations of mathematics at Cambridge in 1939, and there’s a philosophical thread connecting Wittgenstein’s ideas to the test. Wittgenstein’s later philosophy emphasized meaning as use: we understand words through how they’re deployed in practice, not through abstract definitions. The Turing Test is essentially Wittgensteinian: if something behaves intelligently in practice, what grounds do we have for denying it intelligence?

It’s a behaviourist approach, operationalizing intelligence through external behavior rather than internal states. Philosophically clever for 1950. But it shows its age now. Large language models can pass—or come close to passing—the test through sophisticated pattern matching, yet they lack many things we’d associate with genuine intelligence: persistent goals, robust world models, the kind of reasoning that generalizes across domains. The test assumed that imitating intelligence required being intelligent. Modern AI reveals that assumption was wrong.

What endures isn’t the test itself but the meta-move: making AI thinkable as an engineering problem rather than a metaphysical puzzle. Turing shifted the conversation from “what is mind?” to “what can machines do?” That opened the field, even if his specific answer aged poorly.

The Full Picture: Turing Beyond Enigma

Turing’s legacy extends far beyond Enigma and the test. Before the war: the Turing machine and theoretical computer science. During the war: Enigma, then speech encryption. After the war: building actual computers—the ACE design, work on the Manchester machines, early programming concepts.

Then, remarkably, he pivoted to mathematical biology. His final papers explored morphogenesis: how patterns form in living things. How do zebra stripes emerge? Why does phyllotaxis—the arrangement of leaves or petals—follow mathematical patterns? Turing used computation to model biological development, decades before bioinformatics existed as a field.

Dermot Turing’s Prof: Alan Turing Decoded (full disclosure: the author is Alan’s nephew, but also a biologist) explains this late work accessibly. It reveals Turing as a renaissance figure: comfortable moving between pure theory and engineering practice, between mathematics and biology, between abstract philosophy and concrete machinery.

And throughout, there’s the philosophical thread: his 1950 paper asked not just whether machines could think but whether they could learn. He believed they could—and in that, he was prescient about neural networks, evolutionary algorithms, and much of modern AI.

The distorted legacy—”Turing broke Enigma”—emerged partly because Enigma stayed classified until the 1970s. For decades, Turing was known primarily for theoretical computer science and the test. When Enigma was declassified, the narrative snapped to codebreaker-hero. His tragic death—prosecution for homosexuality, chemical castration, suicide at 41—made him a symbol of persecution and lost potential.

What got lost was the breadth. Turing wasn’t a specialist. He was someone who could move fluidly between domains, connecting theory and practice, mathematics and engineering, abstract and concrete. That versatility is his real legacy.

Conclusion

The Polish Cipher Bureau broke Enigma’s early versions through pure mathematics. French intelligence connected the dots between nations. Turing mechanized the solution at industrial scale. Y Service provided the data. Bletchley Park provided the culture. Remove any single element, and the system collapses.

This isn’t a story about diminishing Turing’s genius—it’s about understanding what genius actually looks like in practice. Turing was brilliant precisely because he could build on Polish foundations, translate theory into machines, and work within a collaborative system. His real achievement wasn’t solving Enigma alone. It was knowing how to turn individual insight into collective success.

The Turing machine remains foundational to computer science. His work on computability, his early AI philosophy, his mathematical biology—all endure. But perhaps his deepest legacy is this: he showed that the hardest problems yield not to lone brilliance, but to brilliant individuals working within brilliant systems. That’s the lesson we keep forgetting, and the one most worth remembering.

Further Reading

Books:

Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: The Enigma (1983)

Dermot Turing, X, Y & Z: The Real Story of How Enigma Was Broken (2018)

Dermot Turing, Prof: Alan Turing Decoded (2015)

Charles Petzold, The Annotated Turing: A Guided Tour Through Alan Turing’s Historic Paper on Computability and the Turing Machine (2008)

Sinclair McKay, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010)

Sinclair McKay, The Secret Listeners: How the Wartime Y Service Intercepted the Secret German Codes for Bletchley Park (2012)

Adam Zamoyski, Warsaw 1920: Lenin’s Failed Conquest of Europe (2008)