Intoxicate Me Now

AI, Nuclear Weapons, and the Paradox of Intention

Reading about Russia’s nuclear deployments to Kaliningrad and China’s plans to add hundreds of warheads to its arsenal, I’m transported back to 1987. I’m six years old, asking my father about the Pershing missiles being withdrawn from Germany. His reassurance—that the Soviets had “no money to start a nuclear war”—seems quaint now. Today, money isn’t the constraint. The constraint is something far stranger: the logical impossibility of genuine deterrent intentions.

In 1983, philosopher Gregory Kavka posed a thought experiment that cuts to the heart of this problem. A billionaire offers you a million dollars if, at midnight tonight, you genuinely intend to drink a mildly toxic substance tomorrow afternoon. The twist: you get paid based solely on your midnight intention. You don’t actually have to drink the toxin—the money will already be in your account by morning.

Can you form this intention? Try it. Really try to intend to do something you know will be pointless and mildly harmful when the moment arrives. You can’t—not genuinely. You might tell yourself you’ll drink it, even pledge to do so, but you cannot authentically intend to perform an act you know will have no rational basis when the time comes.

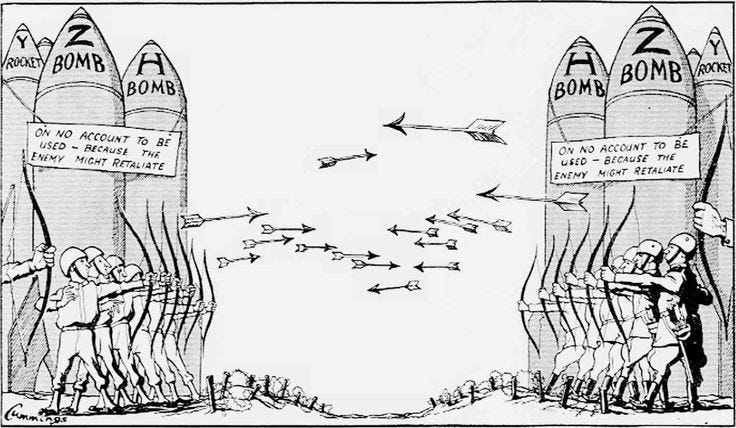

This isn’t just philosophical parlor tricks. Kavka developed this puzzle while analyzing nuclear deterrence, and the parallel is exact. How can we credibly threaten nuclear retaliation after being destroyed? Such retaliation would serve no purpose—our cities would already be ash, our people dead. We would be choosing only to add to the sum of human suffering. No rational agent can genuinely intend to do something so purposeless and destructive.

Yet deterrence depends on exactly this impossible intention.

The Strangelove Solution

The Cold War produced three remarkable films that grasped this paradox with surprising philosophical sophistication. Each offered a different perspective on how humans handle the impossible logic of nuclear deterrence.

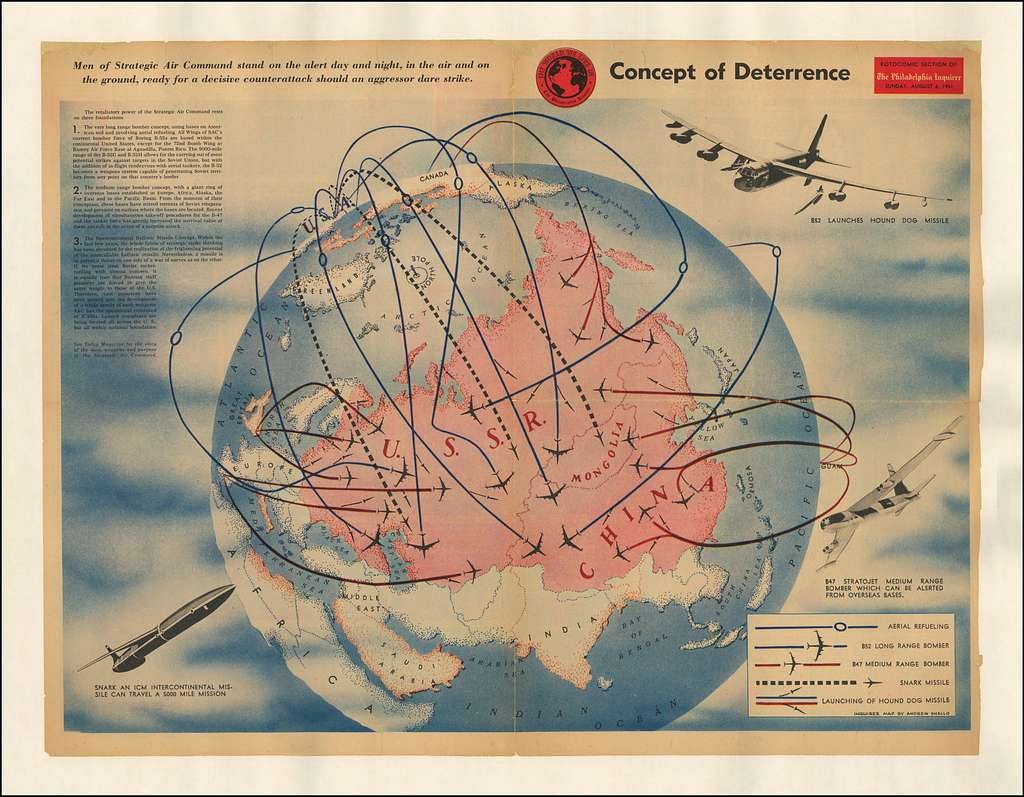

Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 satire Dr. Strangelove presented the ultimate workaround to Kavka’s puzzle through its fictional “Doomsday Machine.” This Soviet device would automatically trigger world-ending retaliation if the USSR were attacked, could not be disarmed, and—crucially—everyone knew this. The machine solves the intention problem by eliminating intention altogether. There’s no agent left to have or lack genuine intentions; there’s only mechanical certainty. As Dr. Strangelove himself explains in the film, the whole point is to remove human meddling from the equation.

That same year, Fail Safe explored what happens when these technological solutions fail. The film follows an accidental nuclear attack on Moscow caused by mechanical error. To prevent all-out war, the American president must order the nuclear bombing of New York to prove the Moscow strike was unintentional. He must genuinely commit to destroying his own city, not as a future intention but as an immediate act. The film shows how technology hasn’t eliminated the paradox—it’s displaced it to even more catastrophic moments of human choice.

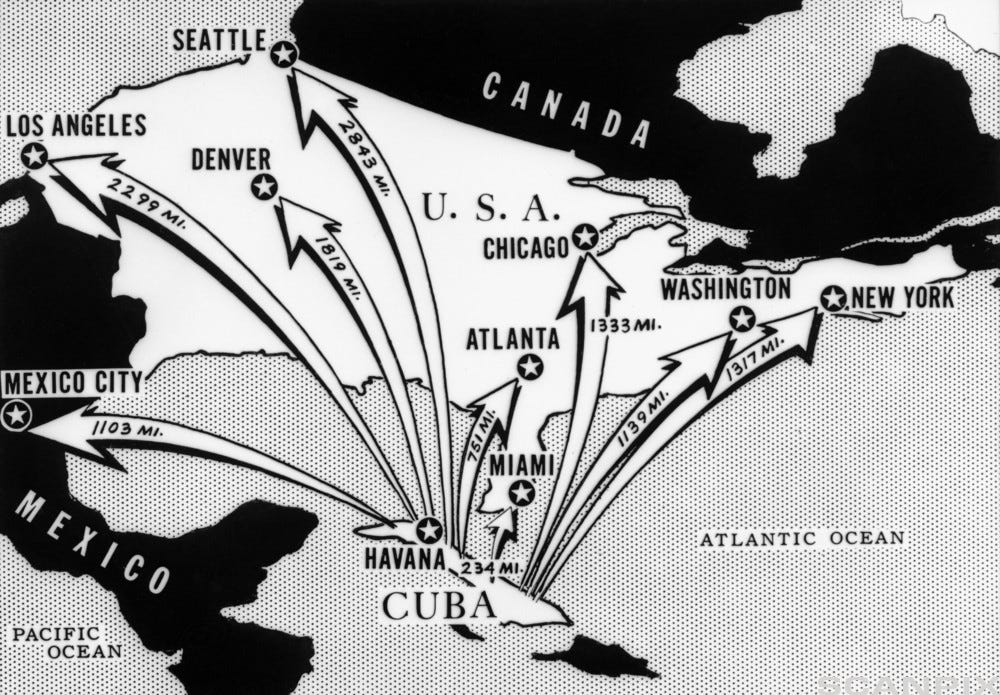

Thirteen Days (2000), depicting the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, shows something entirely different: humans wrestling with Kavka’s paradox in real time. The film dramatizes the ExComm meetings where Kennedy’s advisors struggle to find a response that is both credible and rational. They’re essentially trying to figure out how to credibly threaten actions they desperately hope never to take. They succeed not by solving the logical problem but by maintaining constant communication—establishing what would become the famous hotline between Washington and Moscow. They acknowledge the game is impossible and develop workarounds through human dialogue and back-channels.

Why Deterrence Worked Anyway

Here’s the peculiar thing: the Cold War’s deterrence framework functioned despite being philosophically incoherent. Or perhaps it functioned because of that incoherence. The logical impossibility forced constant human attention and creativity. Leaders couldn’t rely on rational decision theory because the problem had no rational solution. They had to improvise, communicate, maintain back-channels, engage in elaborate signaling.

The system worked because humans are remarkably good at something machines cannot do: holding contradictory beliefs, engaging in useful self-deception, maintaining intentions we know we cannot rationally execute. We can make ourselves temporarily irrational in service of longer-term rationality. We can, through various psychological mechanisms, form something close enough to genuine deterrent intentions that the system holds.

This is where the distinction between human and machine “intention” becomes crucial. Human intention is a complex psychological state involving temporal awareness, emotional commitment, and the capacity for self-contradiction. When I intend to retaliate, that intention exists in a rich context of fear, anger, duty, and doubt. I can hold this intention even while hoping never to execute it. A machine’s “intention,” by contrast, is simply a programmed response—an if-then statement without the phenomenological depth that makes human intention both paradoxical and flexible.

The Multipolar Breakdown

But this delicate balance is now collapsing. The neat bilateral game of the Cold War has fractured into something far more complex and unstable.

Today’s nuclear landscape operates without clear rules or communication channels. Russia sends drones into Polish airspace—not quite an attack, but clearly a provocation. China builds artificial islands in disputed waters, daring others to respond. Pakistan develops tactical nuclear weapons while North Korea pursues an explicitly unpredictable doctrine. Grey-zone operations exploit the vast gulf between conventional response and nuclear escalation. There’s no single hotline, no shared understanding of the game’s parameters.

What worked for two relatively matched players with established communication protocols falls apart when you have multiple actors with asymmetric capabilities and no common framework. The philosophical paradox remains, but the practical workarounds that made it manageable have dissolved.

The AI Temptation

Enter artificial intelligence—seemingly offering a solution to Kavka’s puzzle. An AI system doesn’t struggle with forming intentions it knows will be irrational to execute. Program it to retaliate, and it will retaliate. No hesitation, no last-minute humanitarian concerns, no philosophical paradoxes.

We’re already moving in this direction. The U.S. military is developing AI-enabled command and control systems that can process sensor data and recommend responses in seconds. Russia’s Poseidon nuclear torpedo uses AI for autonomous navigation and target selection. China is incorporating machine learning into its nuclear early warning systems. The justification is always the same: human decision-making is too slow for modern warfare’s compressed timelines.

But this isn’t solving Kavka’s problem—it’s abandoning the very concept of rational intention. We’re building Strangelove’s Doomsday Machine, not as satire but as strategy. We’re removing human agency from the equation, forgetting that the agency, with all its logical contradictions, was what kept the system human.

The push to remove “human bottlenecks” from nuclear command and control treats Kavka’s paradox as an engineering problem rather than what it really is: a fundamental limit on rational decision-making. When we delegate these decisions to machines, we’re not creating more rational actors—we’re creating actors that operate outside the bounds of rationality altogether.

The Man Who Saved the World

On September 26, 1983, Soviet early-warning systems reported that several U.S. nuclear missiles were on their way toward the USSR. The officer on duty, Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, had seconds to decide whether to report the attack and trigger retaliation. Trusting his intuition that the radar reading was a false alarm, he chose not to escalate. He was right — the system had misinterpreted sunlight reflections as incoming missiles. Petrov’s refusal to act mechanically may have prevented global nuclear war.The Deeper Lesson

Kavka’s toxin puzzle reveals something profound about intention, rationality, and human decision-making that extends far beyond nuclear strategy. It shows us that there are situations where rational agents cannot form the intentions that would best serve their goals. This gap between what we should intend and what we can intend isn’t a bug in human cognition—it’s a feature of what it means to be rational.

Current AI development often assumes we want maximally rational, consistent decision-makers. But the nuclear paradox suggests something counterintuitive: sometimes we need agents capable of productive irrationality, of maintaining contradictions, of intending what shouldn’t be intended. Human minds evolved to handle these paradoxes through various forms of self-deception and emotional override. We can make ourselves angry enough, frightened enough, or committed enough to form quasi-intentions that shouldn’t logically exist.

As we rush to automate everything from military decisions to everyday choices, we should remember that removing the capacity for logic doesn’t solve paradoxes—it erases them. The fact that we can’t genuinely intend to drink Kavka’s toxin isn’t a weakness—it’s what makes us rational agents rather than mechanical executors.

The contemporary breakdown of deterrence isn’t just a problem of international relations. It’s a preview of what happens when we try to engineer away fundamental philosophical problems. The messy, illogical, deeply human system of nuclear deterrence worked precisely because it was riddled with paradoxes that demanded constant thought, communication, and creativity.

Perhaps, as we build increasingly sophisticated AI systems, we should pay attention to what Kavka’s puzzle teaches: some problems don’t have solutions—only ongoing negotiations with impossibility. And perhaps that’s exactly as it should be.

The machines we’re building can’t drink the toxin because they can’t truly intend anything at all. They can only execute. In our rush to escape the paradoxes of human intention, we risk forgetting that those paradoxes—maddening as they are—might be the very things keeping us alive.